The autism epidemic is real, and catastrophic

Don't let the denialists whitewash reality, it's downright foolish to pretend today's autism numbers aren't a devastating real rise in the number of affected children

The question is stark: Is autism an ancient and genetic variation that demands acceptance and celebration, or is it new and disabling, triggered by something in the environment that is damaging more children every day?

— Dan Olmsted and Mark Blaxill, coauthors of Denial

NEW YORK, New York—In 2015 Steven Silberman published NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity. Silberman, a former record producer, restaurant critic, and teaching assistant to the poet Allen Ginsberg, created a stir in the autism world and brought the tortured idea that autism has always been with us at exactly the same rate back into the public debate. He described a world in which autism is a “naturally occurring form of cognitive difference akin to certain forms of genius.” The geeks of Silicon Valley? Nikola Tesla? All “blessed” with autism. “Whatever autism is, it is not a unique product of modern civilization. It is a strange gift from our deep past passed down through millions of years of evolution,” Mr. Silberman writes, attempting to erase an epidemic with the stroke of a pen.

The term neurodiversity first appeared in the late 1990s, coined by sociologist Judy Singer. She likened acceptance of diverse ways of thinking to other social acceptance movements taking shape and hoped “to do for neurologically different people what feminism and gay rights had done for their constituencies.” On the surface this appears to be a noble pursuit—what could possibly be wrong with advocating for acceptance? In Wired magazine, Mr. Silberman examined the social revolution he believed was taking shape, as advocates with autism and “others who think differently are raising the rainbow banner of neurodiversity to encourage society to appreciate and celebrate cognitive differences, while demanding reasonable accommodations in schools, housing, and the workplace.”

Mr. Silberman’s message met the needs of the media’s social agenda to make autism normal and resonated both in elite circles and with vaccine injury deniers. Featured in many prominent publications (Forbes, the Washington Post, the New York Times, The Economist, and the New Yorker, to name a few), Silberman won the Samuel Johnson Prize for nonfiction in 2015. A glowing review in The Atlantic praised Mr. Silberman’s book and noted that autism self-advocates “make space for anyone who feels not quite normal.”

Mr. Silberman took it a step further, pinning the survival of our species on our ability to accept neurological diversity, explaining that “the value of biological diversity is resilience: the ability to withstand shifting conditions and resist attacks from predators. In a world changing faster than ever, honoring and nurturing neurodiversity is civilization’s best chance to thrive in an uncertain future.”

What an absolute load of crap.

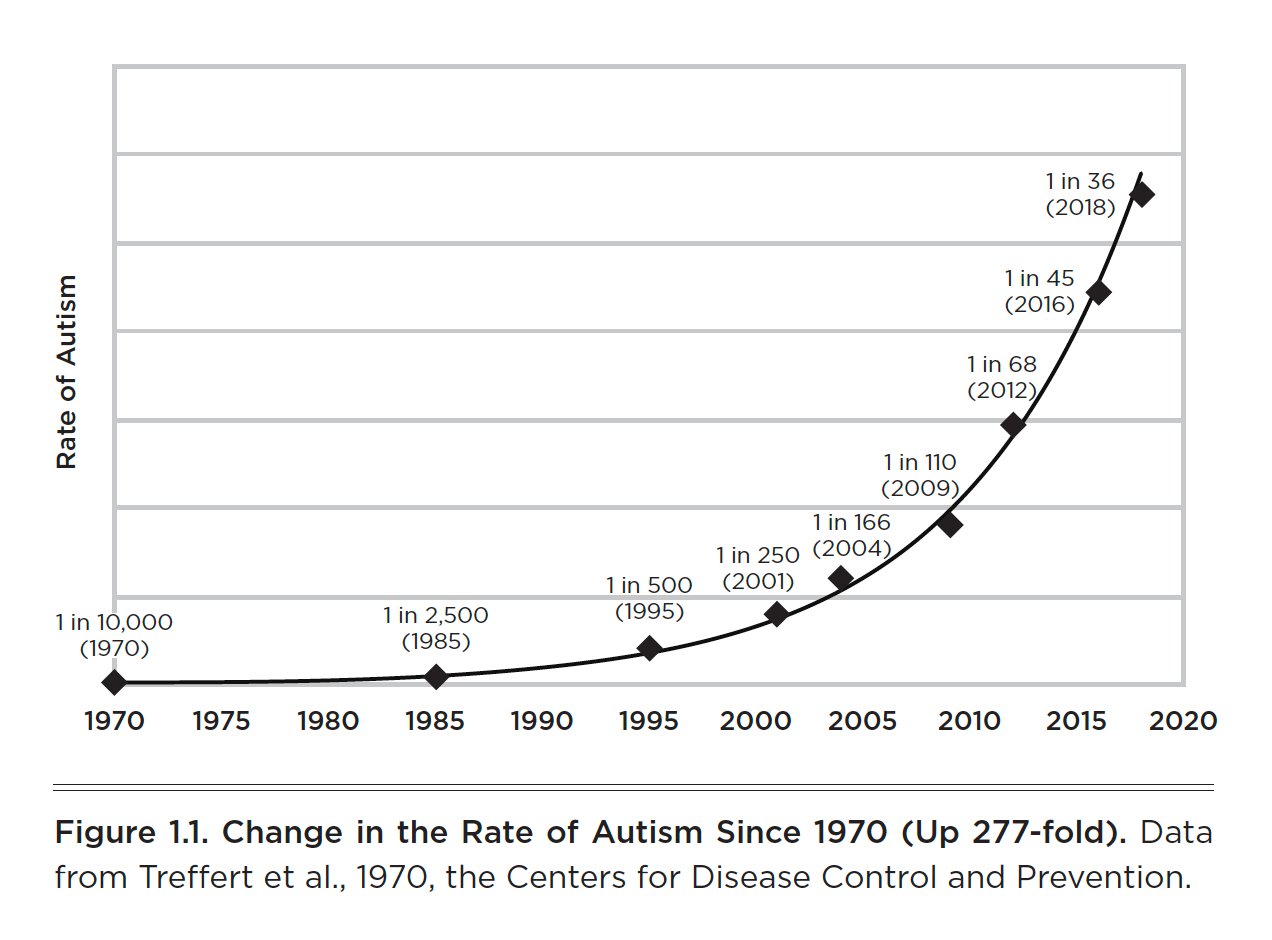

I’m fifty five years old, and as a child I’d never seen or heard of even one peer with autism. Ask any teacher, doctor, nurse, or coach who has been working for three decades or more and you’ll always hear the same thing: something new and very different is happening with children today. My teenage children know dozens of kids with autism, and schools are bursting at the seams with special education classes. When you look at a graph of the change in the rate of autism over time, it’s breathtaking. When I first heard that there were researchers, spokespeople, and experts claiming that the growth in the number of kids with autism was all a big mirage and that these children had always been here, I really couldn’t take it seriously.

Of course, a simple question refutes this narrative:

“Where are all the older adults with autism?”

If Mr. Silberman’s version of history is plausible, you’d need roughly 2 percent of American adults to be exhibiting clear signs of autism. Let’s do the quick math: Fifty-four percent of the US population is over the age of thirty-five. That’s roughly 174 million people. If one in thirty-six of those adults had autism, that’s 4.8 million American adults with autism—4.8 million adults over the age of thirty-five who have a disabling condition that makes independent living a challenge for all but the mildest of cases.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., an environmental activist and lawyer, has often discussed the lack of adults with autism, citing his family’s decades-long involvement with the Special Olympics, which he asserts never used to have participants with autism. He asked (in 2017 when the autism rate was one in forty-five), “Why isn’t one in forty-five older people you see walking around the mall, why isn’t one in forty-five wearing diapers and wearing a football helmet, and having seizures, head banging and stimming?”

There is no data anywhere that supports an adult autism number anywhere close to 4.8 million. To accommodate that many individuals, you’d have nursing homes, group homes, and mental institutions overrun with adults with autism. The best data I could find about housing for adults with disabilities was in Canada, where a federal health system makes data more trackable. In Canada’s largest province, Ontario, there are 13.6 million people. Adults over thirty-five make up 7.34 million people, which at a rate of one in thirty-six would mean 204,000 adults with autism. And how many group home spaces does Ontario offer for adults with all forms of developmental disabilities? Eighteen thousand. Keep in mind, autism is only one form of developmental disability and represents well under half of all cases. Ontario doesn’t have more beds, because they don’t need more beds (yet) —there are nowhere near that many adults with autism. In fact, forty-two thousand adults are being serviced in Ontario for all disabilities, and if the rough math says that if autism is half that number, there are 90 percent of the adults with autism in Mr. Silberman’s world “missing” from Ontario (twenty thousand actually there versus two hundred thousand).

Because they don’t exist.

A single book destroys this fable

If that simple math isn’t enough to convince you, a book was published in 2017 that absolutely annihilated this absurd narrative: Denial: How refusing to face the facts about our autism epidemic hurts children, families, and our future, was written by former UPI investigative journalist Dan Olmsted (Rest In Peace, Dan) and Harvard MBA and autism parent Mark Blaxill. Apparently, the authors had similar misgivings about writing an entire book dedicated to a topic that one would hope most people consider to be poppycock, noting that “part of our personal challenge as an autism parent and a health journalist becomes taking the ‘idea’ [that there is no real autism epidemic] seriously enough to debunk it thoroughly, not just wait for history to stomp all over nonsense as it is eventually wont to do.”

Olmsted and Blaxill’s book is so incisive and so clear, and so specifically destructive of Mr. Silberman’s entire thesis (they dedicate many chapters to refuting NeuroTribes), that I will struggle to do the book justice in a lone blog post. What I can do is offer you a few select passages from the book that I think stand alone in painting epidemic denial in the absurd light it deserves:

Epidemic denial doesn’t add up. Take the US population of 124 million in 1931—the year the eldest child in that first report on autism was born. Divide that number by the current autism prevalence of one in sixty-eight children [Note: it’s now one in thirty-six]. There should have been 1.8 million Americans with autism in 1931. There weren’t. We have scoured the medical literature for cases before then, and there are essentially none to be found.

They also provide “since the beginning of time” math, which makes Mr. Silberman’s and other’s claims even harder to accept:

Back up a bit more: how many people have ever lived on earth? About 100 billion by 1931. Again, simple math yields about one-and-a-half-billion autistic individuals who have lived before 1930. Now we begin to glimpse the emptiness behind the Epidemic Denier’s claims. There may have been scattered individuals with enough traits to qualify for an autism diagnosis, but 1.5 billion would have been far more visible. Someone would have said something. Given the distinctive profile of autistic children, it’s impossible that no doctor or social observer commented on their markedly different behavior.

Romanticizing a Devastating Disability

As an autism parent, if I immerse myself in Mr. Silberman’s fictional version of autism and its history for long enough, it all starts to sound sort of fine, if not even a little great. Autism is just a different way of thinking. It’s always been here. People with autism are gifted and have so much to offer the world. Heck, a TV series on ABC, The Good Doctor, brings autism even further into the mainstream—the central character is a doctor with autism who has extraordinary powers to heal.

Unfortunately, the Good Doctor is like a guy with a small limp and a cane representing paraplegics to the world. His story is fascinating and compelling but bears little resemblance to the autism most parents, myself included, actually deal with every single day. And on a personal level I resent the way Mr. Silberman, The Good Doctor, and many neurodiversity advocates are romanticizing a devastating disability:

If you “discovered you have autism in college,” you don’t have the autism now afflicting more than one million American children. Including my own son.

Despite what you may have read, the definition of autism has remained remarkably consistent over time. Because autism can’t be diagnosed with a blood test, it’s diagnosed through observation, and anyone possessing enough qualities of autism has autism. The hallmarks of an autism diagnosis include early onset of symptoms (typically before thirty months), an inability to relate to others (called “social-emotional reciprocity”), “gross deficits” in language development, peculiar speech patterns, and unusual relationships with the environment (attachment to inanimate objects, rigidity, etc.)

As Olmsted and Blaxill explain, “Most with an autism diagnosis will never be employed, pay taxes, fall in love, get married, have children, or be responsible for their health and welfare.”In fact, upward of 50 percent of children with an autism diagnosis are unable to speak at all, according to the California Department of Education. A study in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders showed that 28 percent of eight-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) exhibit self-injurious behavior (they physically hurt themselves). Maternal and Child Health Journal published a study showing that kids with autism are twice as likely to be obese. A study inPediatrics showed 35 percent of young adults with autism have never had a job or received any education after high school. The average cost to support an individual with autism over his or her lifetime? $2.4 million.

If those figures aren’t bad enough, a study published in the journal Research in Developmental Disabilities showed that children with autism are also considerably sicker than their non-autism peers. Asthma, skin allergies, food allergies, ear infections, severe headaches, and diarrhea or colitis are all far more likely to be present in a child with autism. In fact, the gastrointestinal problems of children with autism were so much worse than any other group that the study authors thought it deserved special attention, noting

“one finding stood out in particular when we compared the developmental disability groups to each other: Children with autism were twice as likely as children with ADHD, learning disability or other developmental delay to have had frequent diarrhea or colitis during the past year. They were seven times more likely to have experienced these gastrointestinal problems than were children without any developmental disability.”

Recently, National Public Radio reported that people with developmental disabilities are seven times more like to be sexually assaulted and that the assaults typically “happen in places where they are supposed to be protected and safe”—a nightmare scenario for every autism parent.

Finally, and tragically, the organization Autism Speaks estimates that fully one-third of children with autism also have epilepsy, “a brain disorder marked by recurring seizures, or convulsions.” And a European study in 2016 found that people on the autism spectrum “are dying younger than the average person—by 12 to 30 years” with the leading cause of early death being epilepsy. Is this the same happy world Mr. Silberman depicts? Not on your life. Or theirs.

Even Congress Thinks We Have an Epidemic

In 2012 the US House’s Committee on Oversight and Government Reform held a hearing about autism. The name of the hearing? “1 in 88 children [the autism rate at the time]: A look into the federal response to rising autism rates.” Chairman of the Committee Darrell Issa opened the hearing and said, “But right now, if the numbers are accurate, and if they continue to grow from the now 1 in 88 that in some way are ASD affected, we, in fact, have an epidemic. It could be that some of the 1 in 150 at the start of the previous century was too low; that, in fact, people were simply not diagnosed. But few people believe that.” Dan Burton, a congressman from Indiana, added, “we’ve gone from 1 in 10,000 children to be autistic to 1 in 88. It is worse than an epidemic; it is an absolute disaster.”

Carolyn Maloney, a congresswoman from New York, was even more emphatic:

Autism is becoming a growing epidemic in the United States, and it definitely needs to be addressed. . . . Now, the numbers that he pointed out earlier, that it used to be 1 in 10,000 kids got autism, it’s now 1 in 88, and I’d like to ask Dr. Boyle [a CDC employee], why? And I don’t want to hear that we have better detection. We have better detection, but detection would not account for a jump from 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 88. That is a huge, huge, huge jump. What other factors could be part of making that happen besides better detection? Take better detection off the table. I agree we have better detection, but it doesn’t account for those numbers.

Our own elected representatives seem to know the truth, and yet people like Mr. Silberman continue to be featured all over the media.

No Epidemic, No Responsibility

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. delivered a compelling take on why he thinks epidemic denialism remains in the public conversation. In a pointed essay discussing Mr. Silberman’s book in 2015, Mr. Kennedy stated:

A threadworm tactic employed for a decade by Big Pharma and the Center[s] for Disease Control (CDC) and their allies to combat the scientific evidence that the autism explosion is a manmade epidemic of recent origins has been to hint that there is no autism epidemic at all. Public health agencies maintain a disciplined refusal to call the disease’s sudden explosion an “epidemic” or “crisis” and actively discourage scientific investigations of environmental triggers. “You will never ever hear CDC characterizing the autism explosion as a crisis or an epidemic,” Dr. Brian Hooker, Simpson University epidemiologist, said. “So long as there is no epidemic, no one needs to look for the environmental trigger.” All this accounts for the giddy excitement among Big Pharma funded media outlets at the debut of Steve Silberman’s book, NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity. Parroting Pharma’s old propaganda canard, Silberman suggests that autism is a wholly genetic psychological ailment that has always been with us in prevalences similar to those found today. Silberman argues that we never noticed autism until recently, because affected persons with the illness were formerly stashed in mental institutions or misdiagnosed.

Mr. Kennedy concludes that “Silberman’s overarching message is that we should stop investigating the environmental cause of the autism epidemic—and potential cures—and simply celebrate humanity’s neurodiversity mosaic. This, of course, is all crackpot stuff.”

Olmsted and Blaxill offer up their own take on why by asking, “Who benefits?”

The first question we need to ask is the inevitable one of self-interest: Cui bono? Who benefits from this unconscionable failure to admit and address the simple truth? Given the magnitude of the autism problem, it’s not surprising that powerful interests would look for ways to avoid being blamed for the problem and, even worse, being held accountable in some fashion—financial or otherwise. As we wrote in the book’s first sentence, trillions of dollars are at stake, including billions in profit, stock prices, bonuses, and liability. The dollar signs associated with the epidemic are so large that it’s worth billions for the prime suspects to evade accountability.

The Epidemic Denial Food Chain

Sitting atop the epidemic denial food chain is one man—Dr. Paul Offit. On the surface there’s no reason Dr. Offit should have much of an opinion about autism, or ever be quoted about autism by the mainstream press, given that his area of expertise is . . . vaccines.

Dr. Offit is a professor of “Vaccinology” at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and personally made tens of millions of dollars when one of his inventions—a rotavirus vaccine—was accepted onto the US recommended vaccine schedule. Dr. Offit has no formal training in anything to do with autism, but that hasn’t kept him from writing books about autism (Autism’s False Prophets: Bad Science, Risky Medicine, and the Search for a Cure), and he’s often quoted in the media discussing autism. In 2010 the Age of Autism blog voted Dr. Offit “Denialist of the Decade” for the 2000s. Here’s a typical quote from Dr. Offit about autism’s rate:

It’s not an actual epidemic. In the mid-1990s, the definition of autism was broadened to what is now called autism spectrum disorder. Much milder parts of the spectrum—problems with speech, social interaction—were brought into the spectrum. We also have more awareness, so we see it more often. And there is a financial impetus to include children in the wider definition so that their treatment will be covered by insurance. People say if you took the current criteria and went back 50 years, you’d see about as many children with autism then.

In Dr. Offit’s world there is no problem here. Things are as they always were; we just understand it better. And if there’s no epidemic, there is no environmental trigger, because why have a trigger if something hasn’t actually grown? Said differently:

Denying the autism epidemic is to deny the suffering of millions of children and their families and also to deny the exploration into the true cause so the epidemic might end.

But what is Dr. Offit’s real motivation? In my opinion, the autism epidemic is the single biggest threat to the vaccine program in its current form. If vaccinations are triggering autism in one in thirty-two children, the risk-reward equation for the vaccine program is destroyed. On the other hand, if autism has always been with us, vaccines couldn’t possibly be playing a role.

Dr. Offit is a public mouthpiece with deep financial ties to one company in particular: Merck, the largest vaccine maker in the world. In fact, Dr. Offit is the Maurice R. Hilleman (the same Maurice Hilleman who invented the MMR vaccine) Professor of Vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, a chair endowed by Merck. Is it really that hard to understand why he is the go-to media contact for epidemic denial quotes?

Dr. Offit isn’t alone in providing convenient sound bites, commentary on studies, and, at times, primary research to maintain doubt about autism’s increase. Dr. Peter Hotez, Dr. Eric Fombonne, and Dr. Paul Shattuck are three other media-friendly mouthpieces with deep ties to the vaccine industry who are typically treated in the mainstream press like objective, expert witnesses on any stories dealing with autism.

In the case of Dr. Hotez, perhaps the most quoted “expert” on vaccines and autism in recent years, he’s actually a patent holder of several experimental vaccines. Dr. Fombonne, in addition to authoring one of the most mystifyingly poor studies on the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, has also served as an expert witness for vaccine makers, testifying against the parents of vaccine-injured children in court. Dr. Shattuck was a Merck Scholar and has received grants from the CDC of more than $500,000 to fund his research. Objective experts? Not even close. Do they “benefit” from denying an epidemic? Of course they do, as Blaxill and Olmsted so eloquently explain:

The People who benefit most from Autism Epidemic Denial are those who make the toxins and orchestrate the exposures that, however inadvertently, have caused the epidemic. They benefit, it should be not be necessary to say, first by making money and then by avoiding culpability in the forms of legal, financial, and possibly even criminal liability.

The World’s Autism Authority

In NeuroTribes Mr. Silberman praised the work of Dr. Bernard Rimland, a pioneering psychologist whose famous 1964 book, Infantile Autism, destroyed the idea forever that autism was the result of emotionally distant parents. Mr. Silberman’s choice to lionize Dr. Rimland, while completely appropriate given his immense contributions to the field of autism, is also devastatingly ironic, given that Dr. Rimland was also the earliest and most public voice to challenge a creeping dynamic in the autism debate that first appeared in the mid-1990s: epidemic denialism.

Dr. Rimland, who founded both the Autism Society of America and the Autism Research Institute, was the foremost authority on autism during the decades of the 1980s and ’90s, and until his passing in 2006. In fact, he was the pioneer of biomedical intervention, which many parents have used to recover their children. By the mid-1990s he was seeing incontrovertible evidence of a massive uptick in the number of children with autism, writing as early as 1995 an essay titled, “Is there an autism epidemic?” Dr. Rimland’s response was simple and straightforward:

“Yes! There clearly has been a sharp increase in the number of autistic children.”

By 2000 Dr. Rimland could hardly keep up with an ever-increasing number of children with autism, as well as an ongoing attempt by some to muddy the waters. In that year he published a now famous essay in the Journal of Nutritional & Environmental Medicine, in which he stated:

While there are a few Flat-Earthers who insist that there is no real epidemic of autism, only an increased awareness, it is obvious to everyone else that the number of young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) has risen, and continues to rise, dramatically. . . . The evidence was compelling in 1995, and is overwhelming in 2000. Nevertheless, I read and hear daily about professionals, including many regarded as authorities on autism, who assert that there is no real increase in the autism population. . . . I saw the word autism for the first time in the spring of 1958, five years after I had earned my PhD in psychology. . . . I have heard similar tales from many physicians as well as special education teachers and school administrators whose experience dates back to the early 1970s and before. Autism was truly rare in those days.

Three Main Arguments by Deniers

While Dr. Rimland was arguably the most well-known researcher in the autism community when epidemic denialism first emerged in the mid-1990s, his words alone may not be enough to convince everyone. It’s important to look at the actual data, details, and published studies, of which there are plenty.

Epidemic deniers offer up three separate but related explanations for why they believe autism has always been with us at the same rate: that diagnosis has improved, that autism is a reclassification of mental retardation, and that the definition of autism has expanded. Each explanation sounds plausible on the surface but is decimated by facts and published science. And each of the three commonly used explanations is easily testable, so let’s see what the evidence shows. But first, let’s establish a baseline.

Establishing a Baseline in Wisconsin

In 1970, in the Archives of General Psychiatry, a baseline for autism’s prevalence was established.Using data from Wisconsin, Dr. Darold Treffert and colleagues sought to “identify the incidence and prevalence of childhood schizophrenia and infantile autism in an entire state population age 12 and under.” This was the first time a thorough process had been undertaken to identify the autism rate, and Dr. Treffert and his team looked at roughly 899,000 kids. His finding: 0.7 children per 10,000 “fit the definition of classic early infantile autism.”

This is the study where the widely used “1 in 10,000” figure comes from.

It’s worth noting that Dr. Treffert reported the qualities utilized to categorize a Wisconsin child as having autism:

Classic infantile autism which excludes organicity and is characterized by early onset, withdrawal and inability to relate, speech problems, suspected deafness, and need for sameness. [my son would have met all these criteria].

Dr. Treffert’s study also correctly identified a wide disparity in the gender ratio of autism, noting that boys outnumbered girls 3.4 to 1, and also found that parents of children with autism had achieved “high educational attainment” and had “low incidence of mental illness.” The study was exceptionally thorough and had access to the entire mental health infrastructure of Wisconsin, including any facility where a child exhibiting symptoms of a mental disorder would be seen.

Dr. Treffert felt “because of the complex nature of the disorder, the difficult differential diagnosis, and complicated disposition planning, that in a five-year period it was highly unlikely that any case of childhood schizophrenia or infantile autism in the 12-and-under age group would not have been seen in one of the above settings.” If Mr. Silberman’s view of the world were accurate, there should have been more than eighteen thousand children with autism found in Wisconsin. Dr. Treffert and his team found just over sixty.

Fast-forward forty-five years, and Dr. Treffert commented on the autism epidemic for the Wisconsin Medical Society in a blog post in 2015. While he felt that some of the increase in autism might be due to widening criteria (addressed below ), he also made it clear that he is “convinced there is an actual increase in the disorder . . . And in my view, part of the increase is actually due to some environmental factors (pollutants of various sorts that may contribute as well to a rise in other congenital abnormalities and premature births).”

Let me spell this out, because it’s a really big deal: The very first epidemiologist to analyze the autism rate in Wisconsin in 1970 feels there’s an actual increase in the rate of autism, due at least in part to environmental factors.

Denialist Argument #1: Diagnosis Has Improved

Most people have a hard time internalizing the difference between an autism rate of 3.3 per 10,000 and an autism rate of 277 per 10,000. They know the second number is a lot bigger, but perhaps don’t appreciate the practical application of this difference, so let’s consider a real-world example: In 1987, just before the 1989 inflection point of the autism epidemic, a peer-reviewed study was published called “A Prevalence Study of Pervasive Developmental Disorders in North Dakota,” which aimed to count how many kids had a PDD/autism diagnosis in the entire state. The researchers looked at all 180,000 children under the age of eighteen and determined that North Dakota’s rate of autism was 3.3 per 10,000.

Here’s how the authors summarized their findings:

Of North Dakota’s 180,986 children, ages 2 through 18, 21 met DSM-III criteria for infantile autism (IA), two met criteria for childhood onset pervasive developmental disorder (COPDD), and 36 were diagnosed as having atypical pervasive developmental disorder (APDD) because they met behavioral criteria for COPDD before age 30 months but never met criteria for IA. The prevalence rates were estimated at 1.16 per 10,000 for IA, 0.11 per 10,000 for COPDD, and 1.99 per 10,000 for APDD. The combined rate for all PDD was 3.26 per 10,000 with a male to female ratio of 2.7 to 1.

This was an exceptionally thorough study. The children with an autism diagnosis were assessed in person by a doctor. The data was published in a journal. It was peer reviewed. It was replicable. They found 3.3 per 10,000 kids had autism. Could the researchers have been wrong? Was the real number actually very different? Maybe. Perhaps the real rate was as high as 5 per 10,000 or as low as 2 per 10,000. But ballpark, we are talking about 3.3 out of 10,000 kids with autism or roughly 1 in 3,300.

We now know autism impacts 1 in 36, that’s eighty-three times more kids than the North Dakota study found in 1987. But it’s worse than that if you think about it a different way: In 1987 if you had 1 million kids, 330 would have autism. Today if you have 1 million kids, 27,777 have autism. Let me say that again. In 1987 the rate of autism prevalence meant for every one million kids, 330 had autism. With today’s number, about eighty-three times higher, you’d have almost 28,000 with autism.

If you’re to believe Mr. Silberman and other epidemic deniers, you have to believe that the research on autism prevalence done in 1987 was simply wrong. The researchers in North Dakota missed a ton of kids and wildly underreported the actual number of autism cases. How many kids did they miss?

Well, if the North Dakota researchers found 3.3 kids per 10,000 when they should have found 277 per 10,000 kids with autism, they missed 98.8 percent of autism cases in North Dakota.

That means in 1987 the pediatricians, psychologists, and all of the screeners (not to mention all the parents) in North Dakota were missing 98.8 percent of kids with autism and just letting them slip through the cracks. These kids, all 98.8 percent of them, were sitting right next to you in class, and you, and their parents and doctors, never knew it.

It’s an impossible world, but it’s the one that Mr. Silberman, Dr. Offit, Dr. Hotez, and others want us to believe in.

Back to North Dakota for a second. The scientists and doctors who did that study in 1987, the one showing 3.3 kids per 10,000 with autism, they were damn serious about making sure they were accurate in their count. You see, they followed the same birth cohort, the almost 200,000 kids who made up their original study in 1987, for twelve years. They published a second study, thirteen years later in January of 2000, called, “A prevalence methodology for mental illness and developmental disorders in rural and frontier settings.” The authors concluded:

The results of the prevalence study [the original study in 1987] were compared with the results of a 12-year ongoing surveillance of the cohort. The 12-year ongoing surveillance identified one case missed by the original prevalence study. Thus the original prevalence study methodology identified 98% of the cases of autism-pervasive developmental disorder in the population. This methodology may also be useful for studies of other developmental disorders in rural and frontier settings.

So these researchers went back twelve years later and checked their work. With a couple of hundred thousand kids, they found they had undercounted their original estimate of prevalence of autism in North Dakota by exactly one child. One child! This study alone should silence anyone claiming “better diagnosis,” but there’s more.

The National Collaborative Perinatal Project

Olmsted and Blaxill wrote extensively about this 1975 study in their book, Denial:

It would be awfully convenient to our own argument if the relevant authorities had spent the time and money to create a more modern survey of the autism rate, one that deployed the gold standard of surveillance methods, a prospective study of the autism rate. Such a prospective study would follow a large group of children from birth through childhood, monitoring their development at regular intervals with rigorous consistency to see how they progressed and whether or not they had developmental problems like autism. A prospective study that included autism would tell us what the real autism rate was by carefully tracking a defined population, not by looking back retrospectively trying to identify cases in a population defined after their onset had already occurred. Ideally, to make a compelling case for low rates of autism before the onset of any purported “epidemic,” such a study should have been done somewhere between the recognition of autism in the 1930s and its explosion in the 1990s. Another ideal feature of such a study would be a large sample size—tens of thousands of children tracked from birth to see what percent were diagnosed with autism. This dream study would cull data from computerized medical records and also from neurological, psychological, speech, and hearing exams at every stage in child development. Top medical centers, leading researchers, and strict government supervision would ensure no conflicts of interest. Compare this mythical study to today’s rates and you’d really know if there is an autism epidemic, a mild tick upward, or nothing at all but a change in the gestalt—in the way we describe the varieties of human disability. Oh, wait. That study was done.

Researchers from fourteen different hospitals associated with major universities followed a group of newborns (thirty thousand of them) born between 1959 and 1965. Children received highly structured evaluations on a defined interval from the day they were born until they turned eight years old. The National Institutes of Health (the federal agency responsible for medical research) was clear in explaining why the data from this study was so valuable:

The data were collected as part of a prospective study [following children from birth and reevaluating them continuously], unique in its design and magnitude. The data constitute a repository of information of great value. Books and monographs based on analyses of these data and other publications number in the hundreds. Even so, the possibilities for the development of further knowledge based on this study are immense. It is unlikely that such a study will be undertaken again and it is thus of particular importance that the data be utilized as fully as possible.

To put this in further context, the original name for this study was the “Collaborative Study of Cerebral Palsy, Mental Retardation, and Other Neurological and Sensory Disorders of Infancy and Childhood.” I mention this only to make sure it’s clear to everyone that this study’s primary purpose was to find any aberration in childhood development, of which autism would have stuck out like a sore thumb. As Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has said, missing autism “is like missing a train wreck.”

The National Collaborative Perinatal Project (NCPP) was a momentous undertaking and received its funding directly from the Committee on Appropriations of the US House of Representatives. According to a summary of the study, many mental health professionals testified before Congress on the importance of this study, and the need for scale:

The need for prospective data, systematically recorded, coupled with the rarity of neurological deficits in childhood, made the availability of a large group of pregnant women imperative. . . . The crux of the research effort was to study a large number of cases in great detail in order to evaluate the effects of perinatal factors on the health of the individual child.

“Prospective data, systematically recorded” looking exactly for things like autism; thirty thousand children, a project so big that the “size and complexity of the NCPP required a highly developed and integrated staff to conduct the research developed and directed by the above referenced committees.” Children were screened nine separate times between birth and eight years old; the screenings included pediatrics; psychology; neurology; speech, language, and hearing; and visual screening. At three years old all children were tested for language reception, language expression, auditory memory for digits and nonsense syllables, speech mechanism, speech production, and additional observations—which brings up an obvious question: “What are the chances that a study this thorough would miss autism?” The answer is pretty easy: zero.

Dr. E. Fuller Torrey and his colleagues independently combed the NCPP’s data for their own separate study to examine the impact that maternal uterine bleeding could have on mental disorders. The authors noted that “approximately 4,000 separate pieces of information have been collected on each pregnancy and its outcome.” One of the outcomes they were looking for—autism—was therefore closely analyzed. The results of Dr. Torrey’s study, published in the Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia in 1975, found fourteen children meeting the criteria for autism from the NCPP data.

Fourteen children with autism were found in the most comprehensive study of children that’s ever been done in the United States, in a study looking specifically for “neurological and sensory disorders of infancy and childhood,” which is the definition of autism: a neurological and sensory disorder. Those 14 children equate to 4.7 children per 10,000, versus today’s rate of 277 per 10,000, which is fifty-nine times more kids. The NCPP’s rate of 4.7 per 10,000 is consistent with the North Dakota study’s rate of 3.3 kids per 10,000.

If the real rate of autism had been 1 in 36 during the time of the NCPP, the researchers would have missed 98.4 percent, or 819 of the children with autism. They didn’t.

Today Dr. Torrey remains an active scientific researcher. His area of specialization is schizophrenia. I asked him in an interview about this study from 1975, and he told me,

“I find it very hard to believe that the people involved with the study missed that many children [with autism]. They were very thorough.”

I asked him what he felt could account for so many children with autism today. Dr. Torrey was quick to point out that his area of expertise is schizophrenia but that he “suspects that autism, multiple sclerosis, and schizophrenia are the results of an infectious agent in the brain.” I let you think about that…

The better diagnosis argument doesn’t work. The facts don’t support it, studies don’t support it, and common sense doesn’t support it. Even our congresspersons know it’s ridiculous. Remember Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney? She knew better diagnosis was absurd, and the question she was asking in the 2012 congressional hearing was directed at Dr. Coleen Boyle, who happened to be the person at the CDC in charge of tracking autism numbers. Dr. Boyle was under oath, which meant she needed to choose her words carefully. Dr. Maloney wanted to know what—besides “better detection”—could possibly account for all this autism? Here’s the back and forth between Congresswoman Maloney and Dr. Boyle:

Congresswoman MALONEY: What other factors could be part of making that happen besides better detection? Take better detection off the table. I agree we have better detection, but it doesn’t account for those numbers.

Ms. BOYLE: So just to put it in context, better detection is accounting for some of it.

MALONEY: I know some, but what other factors? I don’t want to hear——

BOYLE: Our surveillance program counts cases of autism and establishes the prevalence. It doesn’t tell us all the answers to the questions as to why.

MALONEY: Okay.

BOYLE: So we are doing a number of studies to try to understand the ‘‘why,’’ and one of the things that we’ve looked at, we’ve tried to look at what’s changed in the environment, things we know are risk factors for autism, things like preterm birth and birth weight.

MALONEY: Well, are you looking at vaccinations? Is that part of your studies?

BOYLE: Let me just finish this.

MALONEY: I have a question. Are you looking at vaccinations? Is that part—pardon me?

BOYLE: So there is a large literature, as I mentioned.

MALONEY: Are you having a study on vaccinations and the fact that they’re cramming them down and having kids have nine at one time? Is that a cause? Do you have any studies on vaccinations?

BOYLE: There have been a number of studies done by CDC on vaccinations of—

MALONEY: Could you send them to the ranking member and the chairman here?

BOYLE: Yes.

I think it’s fair to conclude from reading Dr. Boyle’s response, where she discusses “what’s changed in the environment,” that even the CDC understands that better diagnosis is a losing explanation for autism’s stratospheric rise. Unfortunately, spokespeople like Mr. Silberman and Dr. Offit, who continually make their epidemic denial arguments to the press, are never making their comments under oath. Olmsted and Blaxill provide a great eulogy to the better diagnosis argument:

Against the idea of this hidden horde of autistic adults we’d like to repeat the commonsense test that Kanner’s eldest case was born in 1931 [for his work published in 1943], and that despite his frequent writing about the condition there is no evidence of any older person ever being referred to him or his associates. . . . We believe Kanner’s report should have generated a flood of people of all ages. A hidden horde should have spilled out into the open, with rediagnoses and recognition—and not just of children.

And they never did, because they didn’t exist.

Denialist Argument #2: Autism Is a Reclassification of Mental Retardation

The autism epidemic appears to have begun in the late 1980s. The recognition of the epidemic didn’t emerge until the mid-1990s, and the “shot heard around the world” about autism came from a 1999 report issued by the California Department of Developmental Services (CDDS) titled “Changes in the Population of Persons with Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders in California’s Developmental Services System: 1987 through 1998.” The report confirmed what many felt they were seeing: Autism cases in the California system had nearly quadrupled in just ten years, while all other mental disorders had remained flat. This was hard evidence from California, the state that was viewed as the most precise on tracking autism cases. Olmsted and Blaxill explain what a shock this report really was to conventional thinking about autism:

A credible report from a large state that found the rate of severe autism almost quadrupling in a decade with no obvious explanation made a big splash. That was in part because it confirmed what many were feeling—that there were simply lots more cases of autism. This was a direct challenge to autism orthodoxy—that autism was a genetic disorder that was not susceptible to the kind of sudden increase the California numbers showed. Not surprisingly, an orthodox response to this challenge popped up quickly.

Olmsted and Blaxill are referring to a report—a classic example of “distracting research” —published in 2002 in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder that allowed the flawed theory of diagnostic substitution to take flight, before it quickly crashed and burned forever. Researchers from Kaiser Permanente reanalyzed the California numbers from the CDDS’s 1999 report, and claimed the data showed “changes in diagnosis account for the observed increase in autism.” Said differently, the researchers concluded there was no real autism epidemic, nothing for anyone to worry about.

Diagnostic substitution as a credible explanation for the rise in autism cases experienced a very short shelf life. Data from California, Minnesota, and the US Department of Education quickly repudiated the diagnostic substitution argument, but first the authors of the 2002 study had to retract their results, after a methodological flaw was pointed out to them by Harvard MBA and coauthor of Denial Mark Blaxill. Dr. Lisa Croen, the lead author of the 2002 study implying no autism epidemic, reevaluated her data and concluded that, after taking into account Mr. Blaxill’s criticisms (which he published in a scientific journal), “diagnostic substitution does not appear to account for the increased trend in autism prevalence we observed in our original analysis.”

Let me highlight this important development: The one published article that supported the “diagnostic substitution” article was dead on arrival. In the meantime, researchers at the UC Davis MIND Institute published a report in 2003 (funded by a one million dollar emergency grant from the California legislature) titled, Report to the Legislature on the Principal Findings from the Epidemiology of Autism in California, and their conclusions left no room for interpretation:

Prior to 1985, autism was believed to be a rare condition with an estimated prevalence of 4–5 per 10,000. . . . One of the most controversial aspects of the DDS Report is whether the significant increase in numbers of Regional Center individuals with autism is due to increased rates of autism or to some other factor. . . . Has there been a loosening in the criteria used to diagnose autism, qualifying more children for Regional Center services and increasing the number of autism cases? We did not find this to be the case. . . . Has the increase in cases of autism been created artificially by having “missed” the diagnosis in the past, and instead reporting autistic children as “mentally retarded”? This explanation was not supported by our data. . . . The Autism Epidemiology Study did not find evidence that the rise in autism cases can be attributed to artificial factors, such as loosening of the diagnostic criteria for autism; more misclassification of autism cases as mentally retarded in the past; or an increase in in-migration of children with autism to California. Without evidence for an artificial increase in autism cases, we conclude that some, if not all, of the observed increase represents a true increase in cases of autism in California, and the number of cases presenting to the Regional Center system is not an overestimation of the number of children with autism in California.

It’s shocking to reread this report over twenty years later, because the conclusions from the UC Davis researchers are so clear and stark: The rise in autism cases is a real rise. Period.

Also in 2003 University of Minnesota researchers analyzed state data and shared their results in a study titled, “Analysis of Prevalence Trends of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Minnesota.” Their conclusions were equally stark:

We observed dramatic increases in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder as a primary special educational disability starting in the 1991–1992 school year, and the trends show no sign of abatement. We found no corresponding decrease in any special educational disability category to suggest diagnostic substitution as an explanation for the autism trends in Minnesota.

Finally, in 2005 in the journal Pediatrics, Dr. Craig Newschaffer and colleagues published an analysis of autism rates using US Department of Education data and reached a similar conclusion:

Cohort curves suggest that autism prevalence has been increasing with time, as evidenced by higher prevalences among younger birth cohorts. . . . No concomitant decreases in categories of mental retardation or speech/language impairment were seen.

California, Minnesota, and the US Department of Education all analyzed autism data, and all clearly concluded: Diagnostic substitution is not responsible for the rise in autism rates. If you hear people make the opposite argument in public, they’re uninformed, repeating a lie they heard, or lying themselves.

Denialist Argument #3: The Definition of Autism Has Expanded

To make a potentially confusing series of events simple, let’s just discuss the final outcome. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), in their fourth edition in 1994, added Asperger’s syndrome to the list of autism spectrum disorders. This was an expansion in the definition of autism and created what’s commonly called the “DSM-IV” criteria for autism. In the most generous of analyses, the addition of Asperger’s to the definition of autism in the DSM-IV expanded the number of children by just under 10 percent. A change in numbers? Yes. Enough to explain the mind-numbing increase of eighty times or more in the number of children with autism? Not even close. Blaxill and Olmsted explain:

Adding Asperger’s expanded the effective diagnostic reach of the DSM-IV by roughly 10 percent—enough for an arithmetic increase proportionate to the category expansion but not an exponential one—ten, twenty, one hundred times—that kept rising every year. . . . In all respects, when assessing the impact of adding Asperger’s, all one has to do is make sure to know whether or not Asperger’s cases are added to the numbers one is considering. In most cases, the scary autism numbers we hear aren’t affected very much by Asperger’s cases.

Interestingly, “diagnostic expansion” is the least used explanation for the lack of a “real” increase in the rate of autism, despite the fact that it holds some validity. What the addition of Asperger’s didn’t do to the autism numbers was materially impact their rise. In 2009 a critical study corroborated the limited impact of adding Asperger’s to the criteria for an autism diagnosis, while also sounding a global alarm. A study done by Dr. Irva Hertz-Picciotto of UC Davis’s MIND Institute and her colleagues titled, “The Rise in Autism and the Role of Age at Diagnosis,” made it clear that the rise in the number of children with autism was very real, and the increase “cannot be explained by either changes in how the condition is diagnosed or counted.”In an interview Dr. Hertz-Picciotto was even more emphatic:

There is no evidence that a loosening in the diagnostic criteria has contributed to increased number of autism clients. . . . We conclude that some, if not all, of the observed increase represents a true increase in cases of autism in California. . . . A purely genetic basis for autism does not fully explain the increasing autism prevalence.

Dr. Hertz-Picciotto even called for a renewed focus on studying environmental factors that may be playing a role in autism:

It’s time to start looking for the environmental culprits responsible for the remarkable increase in the rate of autism in California. We’re looking at the possible effects of metals, pesticides and infectious agents on neurodevelopment. If we’re going to stop the rise in autism in California, we need to keep these studies going and expand them to the extent possible. . . . Right now, about 10 to 20 times more research dollars are spent on studies of the genetic causes of autism than on environmental ones. We need to even out the funding.

In 2014 Dr. Cynthia Nevison published what many view as a seminal and definitive work on autism rates, “A Comparison of Temporal Trends in United States Autism Prevalence to Trends in Suspected Environmental Factors,” in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Health. Dr. Nevison also used data from the California Department of Developmental Services and the US Department of Education Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), her study concluded:

The CDDS and IDEA data sets are qualitatively consistent in suggesting a strong increase in autism prevalence over recent decades. The quantitative comparison of IDEA snapshot and constant-age tracking trend slopes suggests that ~75–80% of the tracked increase in autism since 1988 is due to an actual increase in the disorder rather than to changing diagnostic criteria.

In an interview Dr. Nevison expanded on the results of her study:

Diagnosed autism prevalence has risen dramatically in the U.S. over the last several decades and continued to trend upward as of birth year 2005. The increase in autism is mainly real, with only about 20–25 percent attributable to increased autism awareness/diagnoses, and has occurred mostly since the late 1980s.

She also compared the rise in autism to certain environmental exposures:

The environmental factors with time trends that correlate positively to autism include 2 vaccine-related indices: cumulative aluminum adjuvant exposure and cumulative total number of disease-doses by 18 months; polybrominated diphenyl ethers (used as flame retardants); the herbicide glyphosate (used on GM crops); and maternal obesity.

Walter Zahorodny: A savior from an unlikely source

The Centers for Disease Control maintains a monitoring network for autism prevalence across the country, called the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Sites (ADDM). As they explain:

The Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network is the only collaborative network to track the number and characteristics of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other developmental disabilities in multiple communities throughout the United States.Beginning in 2000, the ADDM Network has been tracking the number and characteristics of 8-year-old children with ASD. The program is now in its sixth phase of funding, and the ADDM Network includes fifteen funded sites and one CDC-managed site in Georgia, the Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Surveillance Program (MADDSP).

In March 2022, the ADDM published their most recent data on Autism prevalence, reporting the widely used number of 1 in 36:

For 2020, one in 36 children aged 8 years (approximately 4% of boys and 1% of girls) was estimated to have ASD. These estimates are higher than previous ADDM Network estimates during 2000–2018.

What you wouldn’t know from reading the report is that one of the study’s authors, the college professor from Rutgers University in charge of evaluating autism numbers in New Jersey, just can’t seem to keep his mouth shut. His name is Walter Zahorodny.

Unlike the CDC, who never offers an explanation for the ongoing rise in numbers nor any plan to do anything about it, Dr. Zahorondy continues to do everything he can do to sound a loud alarm (college professors don’t have publicists, so his means of spreading the word is limited.) But, if you take nothing else away from this article, take the words you are about to hear from Dr. Zahorondy, arguably one of the world’s foremost experts on autism prevalence—and, whenever someone tells you the rise in autism isn’t real, just send them his below quotes!

In June 2020 in an interview he provided to SafeMinds, here’s what Dr. Zahorondy said:

Well, the most startling aspect of the report was that in New Jersey … I see the New Jersey rates as being the leading indicator and I was surprised to see that even though our rate overall didn’t go up very dramatically between 2014 and 2016, our rate of autism in boys was at the 5% level. One out of 20 boys have autism. That’s hard to get your head around. Sometimes I find myself checking myself and questioning, why am I saying that? Well, I’m saying that because the data are clear that that’s the case. I certainly never thought that I would be identifying such a high rate of autism among children in our state, but that’s certainly the case. I think that would be, from my perspective, the two big findings of this report are that Hispanic children are significantly under-detected in most states and that autism has the leading indicator shows that one out of 20 boys has autism.

Q from SafeMinds: It is, it is shocking. And right now, because of COVID, we’re hearing about flattening the curve, and it’s difficult as a parent of an individual with autism and watching our rate climb, climb, climb, and to be hearing the country talking about flattening curves, and which absolutely everybody wants to happen with COVID, but it’s hard. It’s hard when our rate has been climbing and it doesn’t seem to really get the attention that it deserves. I’m sure you probably feel similarly.

Dr. Zahorondy: Yeah. I guess one of my dominant emotions is frustration because I really have a hard time accepting or understanding why a dramatic escalation in autism prevalence isn’t experienced as an important or urgent public health issue. How can we say that 3% of the population, 3% of children have autism or 5% of boys have autism and not treat it like an emergency? It’s not a trivial phenomenon. It’s not like we’re talking about individuals who are just somewhat different or have different learning strategies or different temperaments. These children have very significant learning problems and issues related to social involvement and capacity. I just don’t understand why it was shocking for people to realize that 0.6% high autism in Brick Township was an urgent problem, but three times higher rates across the network and 3% in New Jersey isn’t distressing or shocking. If we said that 3% of the children in our country had a hearing impairment or a visual impairment, I think that would be taken to be a real urgent issue that would call for lots of research and lots of investigation and intervention or some complex combination of reasons, I don’t know what to call it, the meme of it’s better awareness seems to have taken hold and the media repeats it over and over, the detriment of understanding the reality of the situation….propaganda, but the CDC, I think, has been just understating the issue, but really it’s the behavior of the press that seems unconscionable to me and that they take for granted that a claim or the assertion of better awareness explains the problem is sufficient. It’s really not a sufficient explanation.

My feeling? Those are ridiculously powerful words from Dr. Zahorondy. So powerful, in fact, I’m going to re-paste a quote right here, it’s all you need to know for the epidemic denialists out there.

“I just don’t understand why it was shocking for people to realize that 0.6% high autism in Brick Township was an urgent problem [which happened in the early 2000s] but three times higher rates across the network and 3% in New Jersey isn’t distressing or shocking. If we said that 3% of the children in our country had a hearing impairment or a visual impairment, I think that would be taken to be a real urgent issue that would call for lots of research and lots of investigation and intervention or some complex combination of reasons…The CDC, I think, has been just understating the issue, but really it’s the behavior of the press that seems unconscionable to me and that they take for granted that a claim or the assertion of better awareness explains the problem is sufficient. It’s really not a sufficient explanation.”

- Dr. Walter Zahorondy, Rutgers University, NJ ADDM Network

An ADDM Whistleblower in Utah

In March 2016 the CDC published ADDM data showing that the rate of autism in the United States had “stabilized” because the data was “largely unchanged” from two years before. The data came from the eleven separate ADDM regional sites where autism data is collected, including Utah (Dr. Zahorondy is in charge of New Jersey), where, one month after the data was published, researcher Dr. Judith Pinborough-Zimmerman filed a whistleblower lawsuit against the CDC.

Ms. Pinborough-Zimmerman wasn’t just a researcher; she’d been the principal investigator for ADDM network in Utah. Her allegations were serious, claiming that she had felt pressure to moderate the autism numbers, helping to make a case that autism numbers were plateauing:

Depositions from Zimmerman and her former colleagues suggest that the alleged data errors were serious and have the potential to produce major differences in reported Utah autism rates.

In December 2017 the CDC quietly released new autism numbers, showing that the number had in fact risen to one in thirty-six. In her Facebook account Ms. Pinborough-Zimmerman made her position on how the CDC has “managed” autism numbers very clear:

Ten years of my research was spent doing ASD prevalence research. We documented staggering changes in prevalence only to be downplayed by the same government who had funded the research. . . . The world is crazy.

Should we believe Ms. Pinborough-Zimmerman and Dr. Zahorondy, or Paul Offit and Peter Hotez? I’ll let you be the judge.

Is Autism Genetic?

I’ve never seen more tortured explanations than the ones used to try to frame autism as being a genetic condition, despite no evidence to support the claim. Literally hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent on the genetics of autism. Scientists have produced endless studies, all of them entirely theoretical.

There is no “autism gene,” and according to geneticist Dr. James Lyons-Weiler, “Studies of genetics have revealed 850 genes associated with autism, but no single gene explains more than 1% of ASD.” What’s more likely is there are genes for things like mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired detoxification, and so on that predispose certain children to reacting more strongly to environmental insults, but the science has yet to be done to prove that conclusively.

When I explain epidemic denialism to close friends of mine who aren’t particularly familiar with autism, they struggle to believe this is actually a thing. “People say there’s not more autism?”

Autism’s massive increase is self-evident to most adults who grew up in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, or even ’90s. Dr. Michael Merzenich has published more than 150 articles in peer-reviewed journals and even won the Kavli Prize (one of the world’s most prestigious prizes in neuroscience) for his work on brain plasticity. He says,

It irritates me to no end that we still argue over whether there is an increase in incidence [of autism]. I think there is lots of evidence for increased incidence. Overwhelmingly it supports that there are things in the environment that are contributing to the rate of incidence. But people still argue.

I concur with Dr. Merzenich; it “irritates me to no end” that we are still fighting in the public about whether there’s been a real rise in the number of children with autism. In my opinion, it shows that vested interests have been effective in doing exactly what they want to do: sow doubt and confusion.

Pouring cold water on the severity of the autism epidemic inhibits the call to action we all need to find causation. It gives scientists on the fence an “out” where they can describe the autism epidemic as “up for debate.” It denies the suffering of so many impacted children, and it’s prevented a redirection of research dollars to find environmental causes.

In the end, saying the autism epidemic isn’t real is simply a lie, and it’s a lie that extends the suffering of so many children.

About the author

J.B. Handley is the proud father of a child with Autism. He spent his career in the private equity industry and received his undergraduate degree with honors from Stanford University. His first book, How to End the Autism Epidemic, was published in September 2018. The book has sold more than 75,000 copies, was an NPD Bookscan and Publisher’s Weekly Bestseller, broke the Top 40 on Amazon, and has more than 1,000 Five-star reviews. Mr. Handley and his nonspeaking son are also the authors of Underestimated: An Autism Miracle and co-produced the film SPELLERS, available now on YouTube.

I remember when Dr Wakefield was charged with malpractice by Brian Deerfield, a 'journalist' working for Murdoch news, whose job it was to find doctors who were not adhering strictly to their prescribed role, and weed them out through the media and the courts. I watched a video clip of some of the parents of autistic children Wakefield had been helping, standing outside the courthouse, not allowed to go in, not allowed to testify. The medical establishment was just that threatened.

"Callous Disregard", Wakefield's book, records verbatim the proceeds of the court case against him. I read that book when it came out. It was a 'kangaroo court'. Wakefield was exonerated, by the way, contrary to what the media wants everyone to believe.

Dr Wakefield also expressed frustration with the way the doctors obfuscated the facts by relabeling some cases of autism as rare neurological conditions so as to avoid the parents' pursuing the issue of the autism/vaccine link.

So definitely, vaccines are a major weapon in the arsenal. Unfortunately not for the purpose of ensuring health. As Denis Rancourt so aptly said, "The role of medicine as an institution in our society is to maintain the dominance hierarchy". Institutions have their own agendas; they exist to perpetuate themselves and to serve those who control them. And those controllers have exposed their agenda pretty clearly in the last few years.

JB, thank you. I used some of your research when I wrote my book in 2021. It is outstanding. I tried to distinguish how much of the increase in diagnosis is severe , non speaking, self-injurious, totally dependent. From the research I did it appears, with the expanded diagnosis criteria, roughly 1/3 is a severe diagnosis.

But the question remains- HOW DO WE GET JUSTICE? How do we get our children the help they need to have control over their bodies? When are our kids going to matter? When is freedom coming?

And why does the state get to come and monitor parents in their home when the state caused the injury and disability? It’s just because we need money. If we didn’t need financial support, we wouldn’t have to answer to their questions and regulations, and could move freely from one district or state. They have forced entire families into captivity to the paternal state.